From Compliance to Opportunity

Navigating the UNTP Digital Product Passport Ecosystem

By: Michael Shea and Nis Jespersen

Introduction

Digital Product Passports are probably about to become part of your everyday life. Whether because you are based in the European Union, or selling products that are being exported to the European Union. Or simply because you are a responsible consumer, concerned that the material is actually organic and that no child labour was used in the manufacturing.

Customs inspectors will be able to check a shipment and automatically retrieve all the origin, scope 3 emissions, sustainable, and compliance certificates associated with the shipment.

Manufacturer, you will be able to automate certification processes, reduce the cost of compliance certification and be able to prove compliance automatically to your customers.

All such information will be made available in products’ passports, just a QR code scan away.

Throughout this article we will work with the following simplified value chain. As we move through each section, we will expand and deepen the value chain as more concepts and components of the Digital Product Passport are introduced.

Simplified clothing value chain.

Background

The term Digital Product Passport was first introduced by the European Commission in its Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP), published in March 2020, outlining DPP as a tool to enhance transparency and sustainability by providing detailed information about products’ composition, origin, and environmental impact throughout their lifecycle.

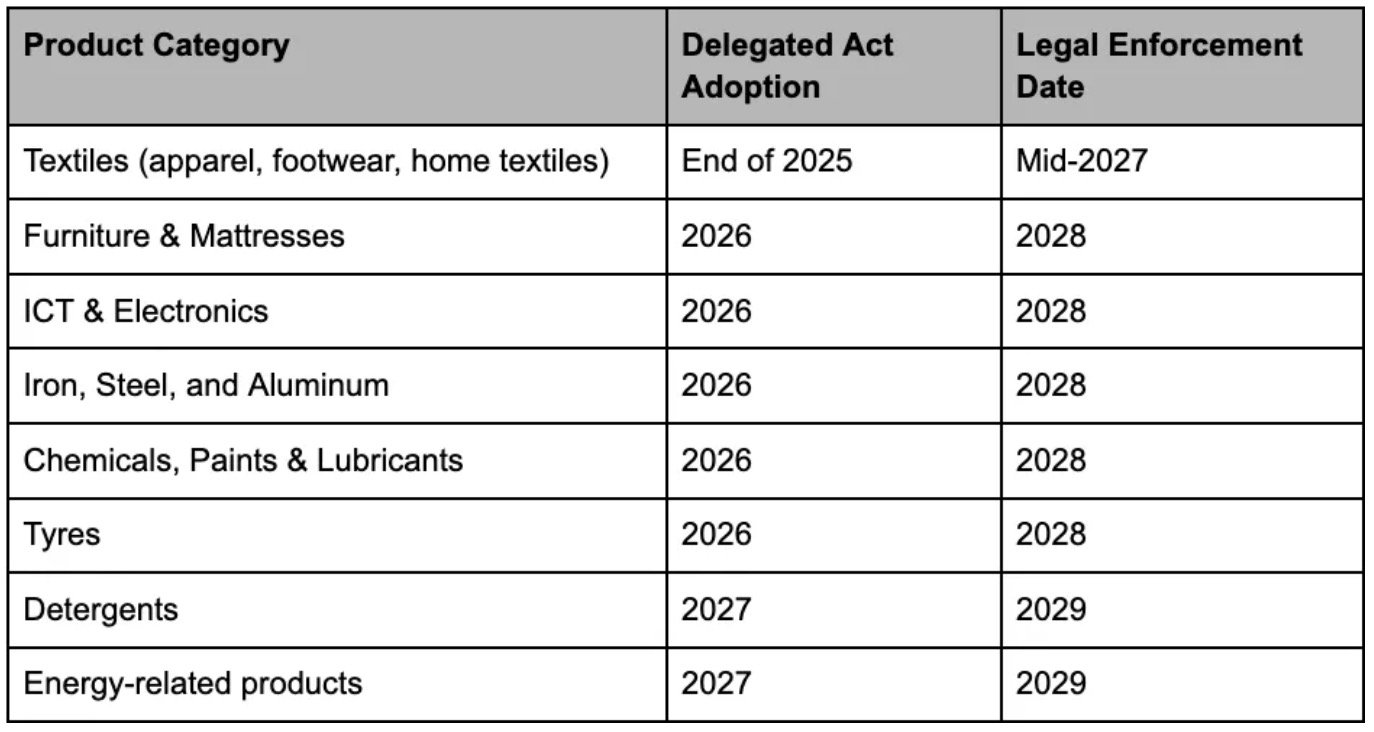

Since then there have been two regulations adopted by the European Commission regarding DPPs, regulating Batteries (February 2024), and Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) (July 2024). During the coming three years additional sectors will be regulated, including Textiles, Mattresses, Electronics, Metals, Chemicals, Tyres, Detergents, and Energy products.

ESPR industry-specific delegated acts and legal enforcement dates.

UN/CEFACT has initiated two projects aligned with objectives of the EU Battery and ESPR regulations: the Critical Raw Materials (CRM) Traceability and Sustainability Project in July 2023 and the UN Transparency Protocol (UNTP) in January 2024. The UNTP effort is to develop an Open Source Protocol that is freely available to organizations and industry trade associations to be the base framework that can be extended by industry sectors to meet their particular sector requirements.

UNTP is the focus of the remainder of this article. Let’s dive in!

Basic Digital Product Passport Usage Scenarios

At different points in time, various actors need to gain information about a product. This will vary depending on the type of product, but includes for example:

Customs and other regulatory agencies at the time of import

Consumers making a purchase decision

Recycler when the product has reached its end of life

At its core, a Digital Product Passport includes a set of claims about a product, issued by the organization marketing it, and made available to the various roles who need to access it. In our simple case our three actors would like to learn more about the clothing. Their need is to access information about the product in order to make a decision.

Various verification experiences.

Let’s take the consumer. They would like to know if the clothing is organic and sustainably produced. Many pieces of clothing today have tags on them indicating this. But how can the consumer trust this information and avoid “greenwashing”?

This is the essential problem which UNTP is here to solve.

In doing so we must first identify the product. Product identification can be at different levels of granularity; the defined granularities within the DPP Regulation are item, batch, and type. In our example, the identifier is an ‘item’ identifier, and to our actors, this is represented by a QR code (or RFID tag) that is attached to the clothing. The Identifier is encoded into the Data Carrier, and both of these data carriers are ubiquitous today and can be scanned with a standard smartphone.

The identifier is the link between the physical clothing item and the digital information that represents the clothing. When the actor scans the QR code the phone automatically retrieves the digital information. This digital information is the Digital Product Passport (DPP).

In our example, the Brand Owner is responsible for creating and managing this identifier. It is also the Brand Owner who creates the product’s Digital Product Passport and the Data Carrier which links it to.

Coming back to our actor who scans the Data Carrier and the DPP is displayed on their phone. Without getting into the technical details at this point, the data which the Brand owner puts into the DPP is all cryptographically signed and linked to the Brand. Through these processes the ability to tamper with, or fake data without detection becomes very difficult. We will go fully in depth on how this is achieved at a later stage.

Why Should Business Care?

At this point, our three actors have their “need” satisfied, they are able to scan the Identifier from the Data Carrier and retrieve the information they need to make their respective decisions. Great! But what is in it for the Brand? This is adding a lot of cost and complexity into their operations. Why should they bother?

The most direct answer is that in order to sell goods in the European Union in the near future the Digital Product Passport is a regulatory mandate. Fashion and clothing brands must comply. That being said, let’s step onto the balcony and take a bigger view of what the concept of a DPP brings to the market.

The European Commission introduced the concept of the DPP to address key societal goals and problems around waste, climate change, and sustainable business practices (re-use and circularity). There are other key business problems that the DPP also addresses like counterfeiting and substandard part substitution that cost businesses billions of dollars/euros every year.

Counterfeiting is a huge problem in the fashion industry. In 2017 the estimated cost of counterfeiting to the global fashion industry was $450 billion dollars. With the creation of a link directly from the clothing Data Carrier to the DPP the fashion industry now has a mechanism that their customers and customs officials can quickly and easily prove that the product is authentic.

As more businesses and industries start to recognize that sustainable business operations and practices can offer strategic operating benefits and as these are integrated into business models the ability to have traceability up their supply chains will be paramount. The DPP is the vehicle that enables this visibility.

Material Sourcing

Product manufacturing and source materials.

A value chain is a series of steps building continuously increasing specialized products. In our example, a manufacturer sews source fabric into clothing. Capturing this step is essential to gain a proper understanding of a product’s full origin.

The source material is in itself a product, and must be described with its own Digital Product Passport (DPP). The manufacturer is responsible for creating a DPP for this stage of the value chain. To capture how it is turned into the final piece of clothing, UNTP includes a Digital Traceability Event document, which describes that “this source material was turned into that product”.

The Digital Traceability Event (DTE) is the third key element of UNTP. The DTE is issued by the manufacturer for every transformational process that the product goes through.

Many of these processes are already being done today, and most are paper based processes. The potential to tamper with documents is very high. The cost to verify and certify is also very high. The result is that in many cases it is not done. Hence fraudulent claims and the green washing problem.

Note that the typical jargon for the actions performed are issuance, subject and verification: When claims documents are digitally signed, that’s called issuance. The subject is who or what the claims are made about, for example a product, person or organization. Verification means confirming the digital signature, which can and should be done at the time of reading the data.

3rd Party Certifications

3rd Party Certification of claims.

So far we have only seen what the brand owner and manufacturers themselves have to say about their products. This is well and good, but falls short of the UNTP promise of countering greenwashing. To be trustworthy, claims have to be backed by relevant 3rd parties which perform the inspections, accounting, and diligence relevant to the given claims.

This is where we introduce the second of the four key elements of UNTP, the Digital Conformity Credential. The Digital Conformity Credential (DCC) is a data structure that is cryptographically signed by a 3rd party when it is issued to the manufacturer. The DCC is the element that is issued by an auditor confirming a claim by the manufacturer and is linked to by the DPP.

UNTP has been designed with the expectation of extension. Each industry sector (or ecosystem) that adopts UNTP will define the claims that are relevant for their sector, and will extend the Digital Conformity Credential to support these.

Let’s continue to develop our story. The Manufacturer has claimed to the Brand owner that the fabric being supplied is organic. This is a self-issued claim. How does the Brand then trust the Manufacturer?

First, let us introduce a new role into our story: an Auditor. Our first auditor in this story is an Organic Inspector. The Inspector has inspected and validated the Manufacturers claims and issued an Organic Conformity Credential for the fabric. This credential is referenced by the Manufacturer in the Digital Traceability Event which allows any actor downstream in the lifecycle to verify the authenticity of the organic claim.

Verification of claims by the downstream actors is very important to eliminate green washing. Please note that verification does not just mean checking that the claims are there, but verifying that the data has not been tampered with. This is done by matching the data to the digital signature. If the signatures do not match, the data has been modified and the credential must be rejected. This is how the green washing problem is addressed.

The ability to tamper is eliminated, and verification is now automated, greatly reducing the cost of inspection. An additional cost benefit is also received by the elimination of the production of paper certificates and credentials.

Manufacturer’s Claims

Adding claims about the manufacturer.

Certain kinds of claims are not suitable or practical to capture at the product level. For example, our manufacturer may adhere to fair labor practices and be certified to not use child labor. These are organization-level claims, and should be expressed with the UNTP Digital Facility Record (DFR) digital document. This is similar to a Digital Product Passport, except that it describes a subject organization rather than a product.

3rd party assertion of organization facility practices.

In the same way as we saw with product assertions, organization assertions should be backed by claims issued by relevant, trustworthy 3rd parties. For example, adherence to anti-child labor practices should be backed by a Conformity Credential issued by an inspection agent overlooking the facility.

In its whole, when presented along with the previously described documents, verifiers can now confirm the level of ethical standards of the manufacturer performing the clothing sewing process.

Why would the Manufacturer bother to change their processes? The biggest motivator is the reduction in costs of audit and certification. Most of the claims in the Digital Facility Record at some point must be attested to by a recognized authority (auditor, governmental department). The current process is time consuming and costly. By converting these processes to consume and produce Digital Credentials these processes can be automated significantly reducing the cost of audit, while increasing the trustworthiness and reducing cost of producing and sharing the certifications.

There are additional benefits for the customers of the manufacturer, with the increased assurance that their suppliers are meeting their contractual and regulatory commitments and since these records are now natively digital and machine processable this can be done at a much lower cost.

We now have digital records from the manufacturer about the product, and their facilities. Why do our actors (Regulator, Consumer, Recycler) trust the data provided? How do they know that the certifications are legitimate and not fraudulent?

Establishing Identity

Anchoring the identity of an upstream actor into a government registry.

Each of the actors in our story represent some form of legal entity; and as verifiers are tracing up the value chain, each step of the way they are essentially asking “says who?”

Ultimately, the root of this “tree of trust” will be reached, at that point there are no more “says who” to ask. The verifier must be comfortable with whomever makes these most fundamental claims; this role is often referred to as the “trust anchor” or the “root of trust”.

Some of the actors along the way might be widely known and trustworthy on their own, for example a country’s customs agency, or a global brand. Many others are not though and so the organization’s claims, although being cryptographically verifiable, are not necessarily trustworthy.

UNTP’s Digital Identity Anchor is a mechanism to overcome this by rooting trust into existing business registries, government identifiers schemes, or certified accreditation bodies. This is done by coupling the subject organization’s digital identifier to the given registry.

In the example above, the Organic Inspector supports his identity with a government entity anchor. This way verifiers know that the Organic Inspector has legal identity in that jurisdiction.

Accreditation

In the 3rd Party Certification section we introduced the role of the Auditor into our story. The Auditor provides an independent assessment of the manufacturer’s claims. This attestation of ‘truth’ by the Auditor allows the downstream actors to trust what has been claimed. We have just covered the ‘Says who?’ question, but this brings another question to the surface, ‘Why should I trust the next guy in the chain?’

Our Organic Inspector has been certified by a National Accreditation Body of the country of the where the Brand will be selling the clothing. In our paper based world once the Auditor has been certified they would receive a seal. This seal is what indicates that the Auditor is ‘trustworthy.’ When the auditor issues a paper based certification, they sign and seal the certificate as ‘true.’

As we move to the digital world, this model is replicated with a digital certificate being issued to the Auditor by the National Accreditation Body. This certificate is used to sign the Organic Conformity Credential. In the EU the eIDAS regulation includes digital seals. This will allow the Auditor to replicate the paper based practice in the digital world.

Accreditation of the Auditor.

General UNTP Building Block Pattern

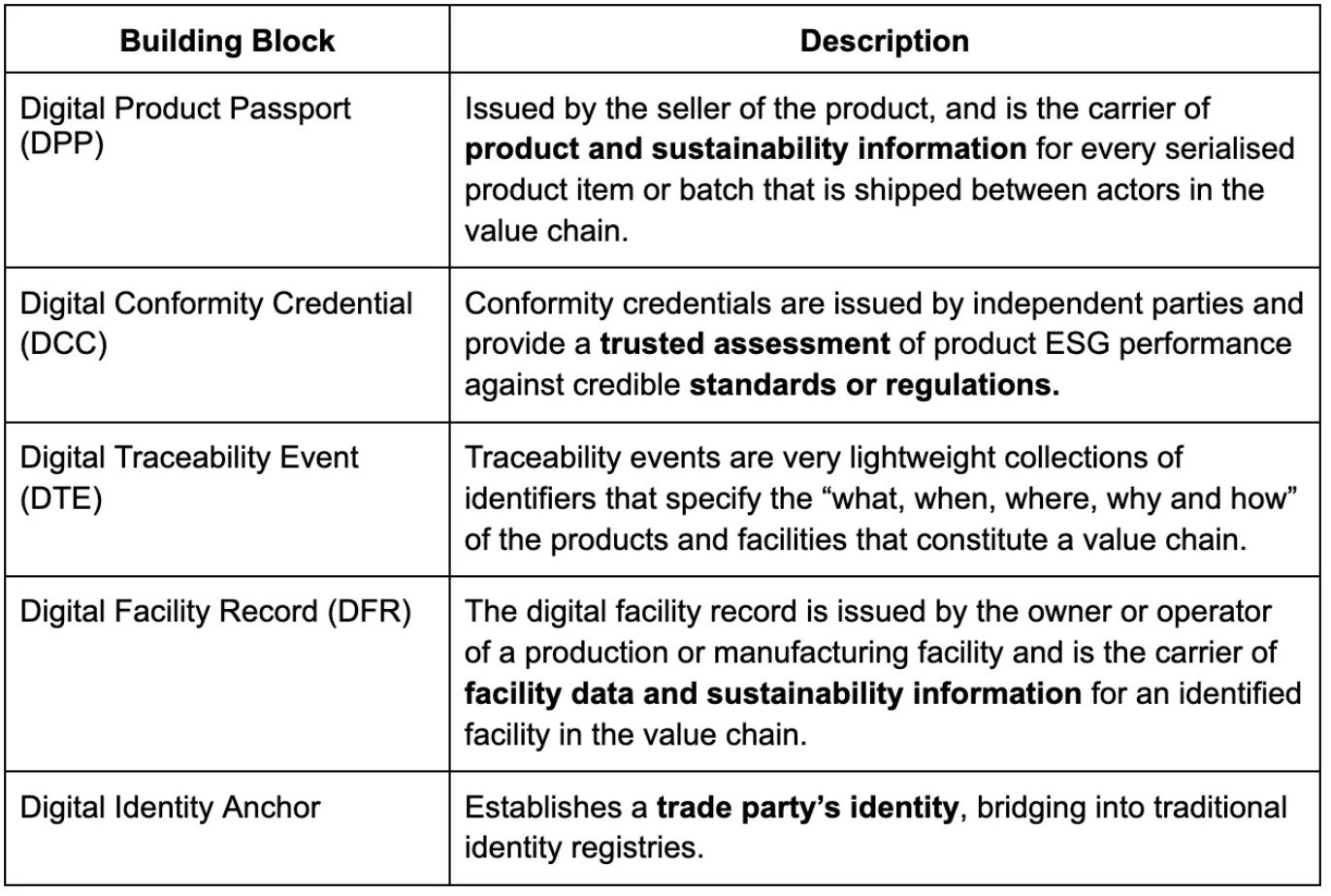

To recap, we have now covered UNTP’s main “building blocks”:

In combination, these building blocks describe aspects of the process of turning a source product or material into an output product: the producer makes assertions about itself and the product, which are supported by 3rd party attestations. This pattern is illustrated simplistically below:

General UNTP pattern for one “link” in the value chain.

This same pattern of document types can be used to describe any step along the value chain; the manufactured output product of one process is the input to the next process:

Applying the UNTP digital documents recursively along the value chain; the manufactured output product of one step is the input to the next.

Icons courtesy of flaticon.com